Sowing seeds of sustainability in Senegal

by Zeke Barlow

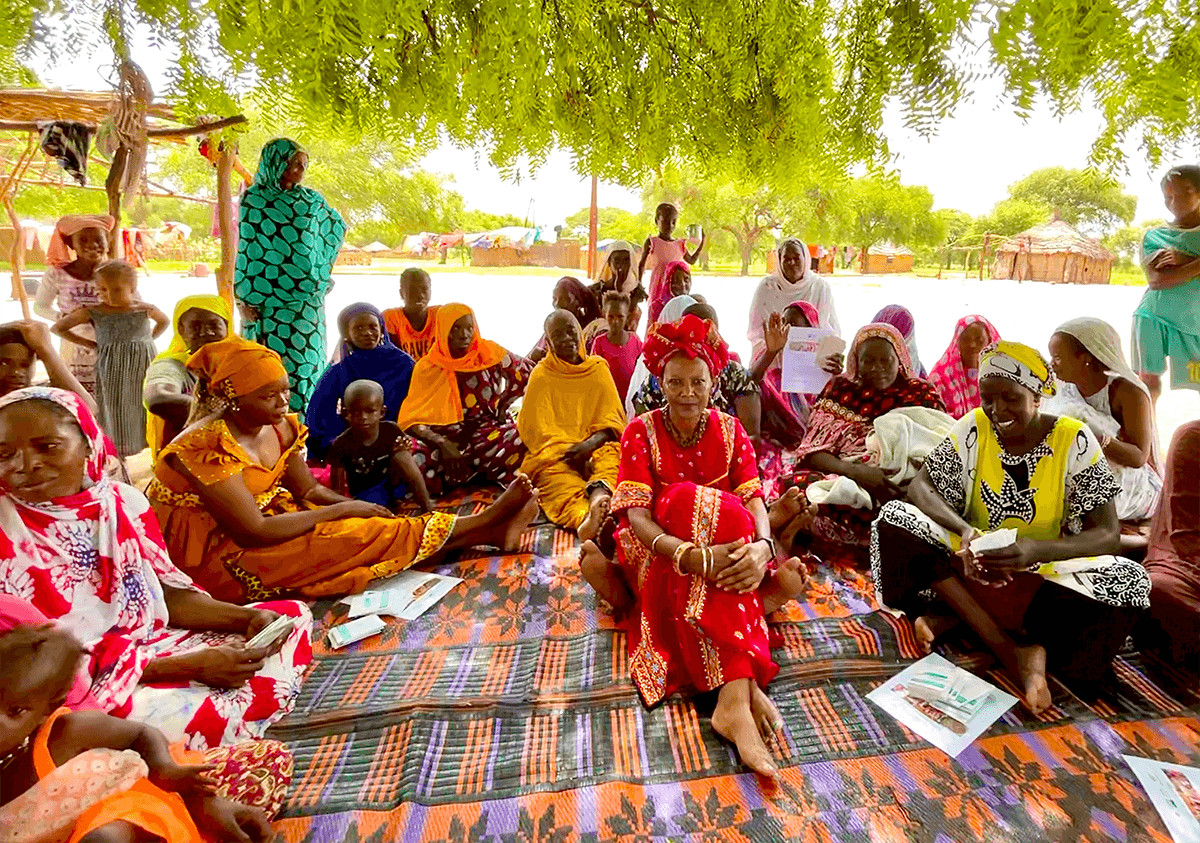

THIEWLE, SENEGAL — Aissit Deme slips off her sandals and sits with the other women escaping the 101-degree heat under the palm-thatched open-air hut, their feet forming concentric circles of henna-dyed artistry. They just came in from harvesting mung beans in the fields, where their dresses looked like a box of crayons exploded onto the green landscape as they quickly plucked the beans from the knee-high plants.

Deme knows that the mung beans are easy to grow in the hot Senegalese sun and that her two children aren’t as hungry after eating them. But since mung beans are a relatively new food source, Deme doesn’t know many ways to prepare them.

Which is why Ozzie Abaye (’92) is here today.

Armed with a stack of mung bean recipes she perfected in her Blacksburg home, five years of research to bring mung beans to protein-deficient Senegal, and decades of agronomy knowledge and outreach, Abaye unpacks the mangos and mint that she bought at the local market.

As women mash garlic in a worn wooden pestle, Abaye talks not only about the ease of growing mung beans, but also their nutritional value. They are high in protein and fiber, which helps kids feel full longer. They are high in folic acid and iron, which promotes breastmilk. They don’t need much fertilizer or pesticides, which saves farmers money. The women nod in agreement as they mix the food together and the young children look at the “toubab” — strangers — sharing the afternoon shade.

Video by Zeke Barlow

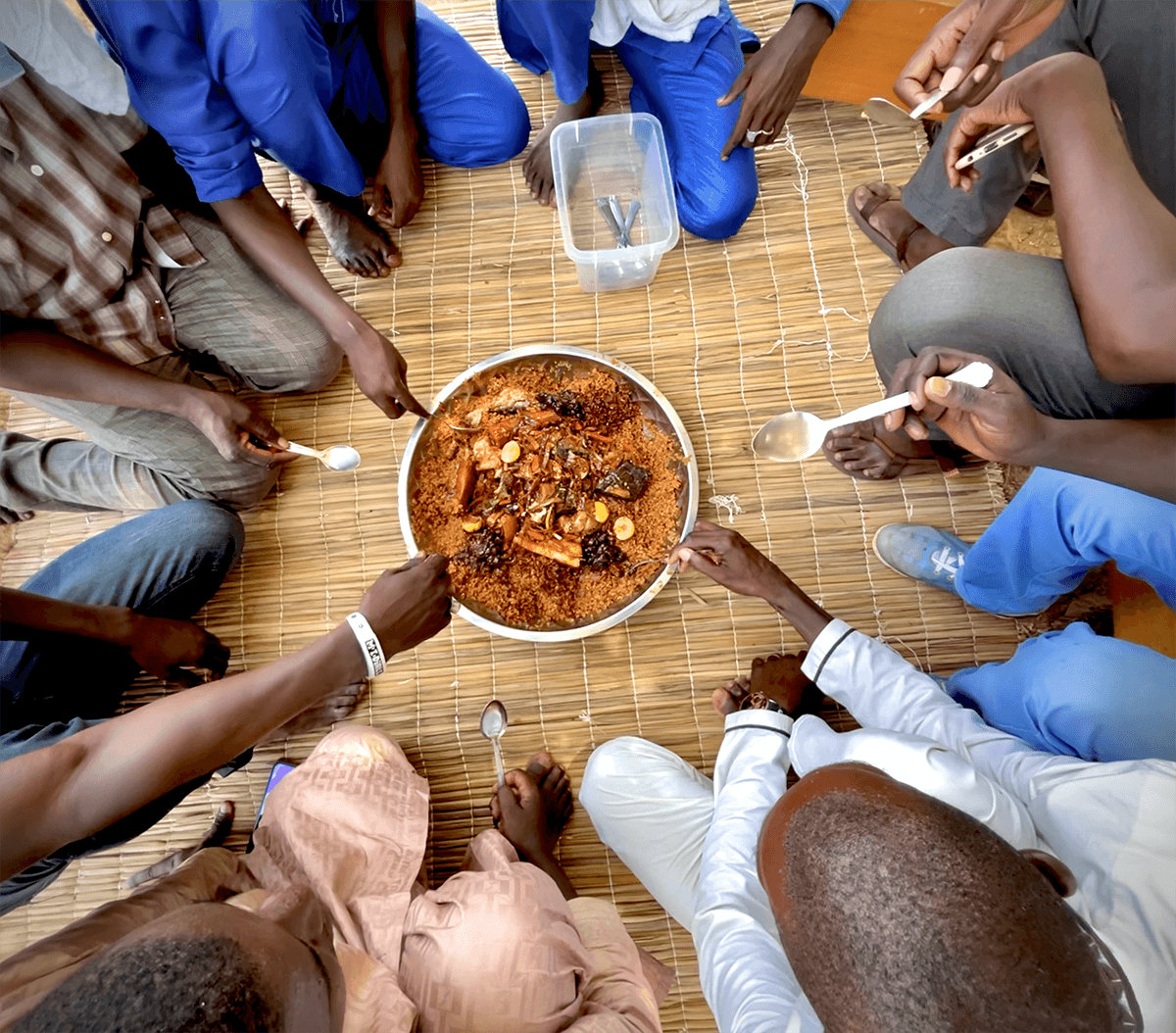

When the mango-mung bean salad is complete — Deme and the others stuff it into baguettes— a relic of France’s colonialization of Senegal.

“Good, good, good,” one woman says in Palor, one of the many Senegalese languages, as she shares the baguette with her child. Deme nods in agreement.

“The first time I had it, I didn’t know how to cook it, so there wasn’t a lot of interest. But now that we have mung bean recipes, there is a lot of interest. It is needed for the children and now we know how to cook it,” says Deme.

“Now I want to go back to the field and plant the rest of them,” she says.

Enclosed in this tiny bean is not only the fiber and protein that her children need; inside this mung bean is the story of harnessing power of the research, Extension, and education efforts of a global land-grant university. It is a story about the impacts of partnerships with groups like the USDA, USAID, and Counterpart International.

It is a story of how agriculture can change the world.

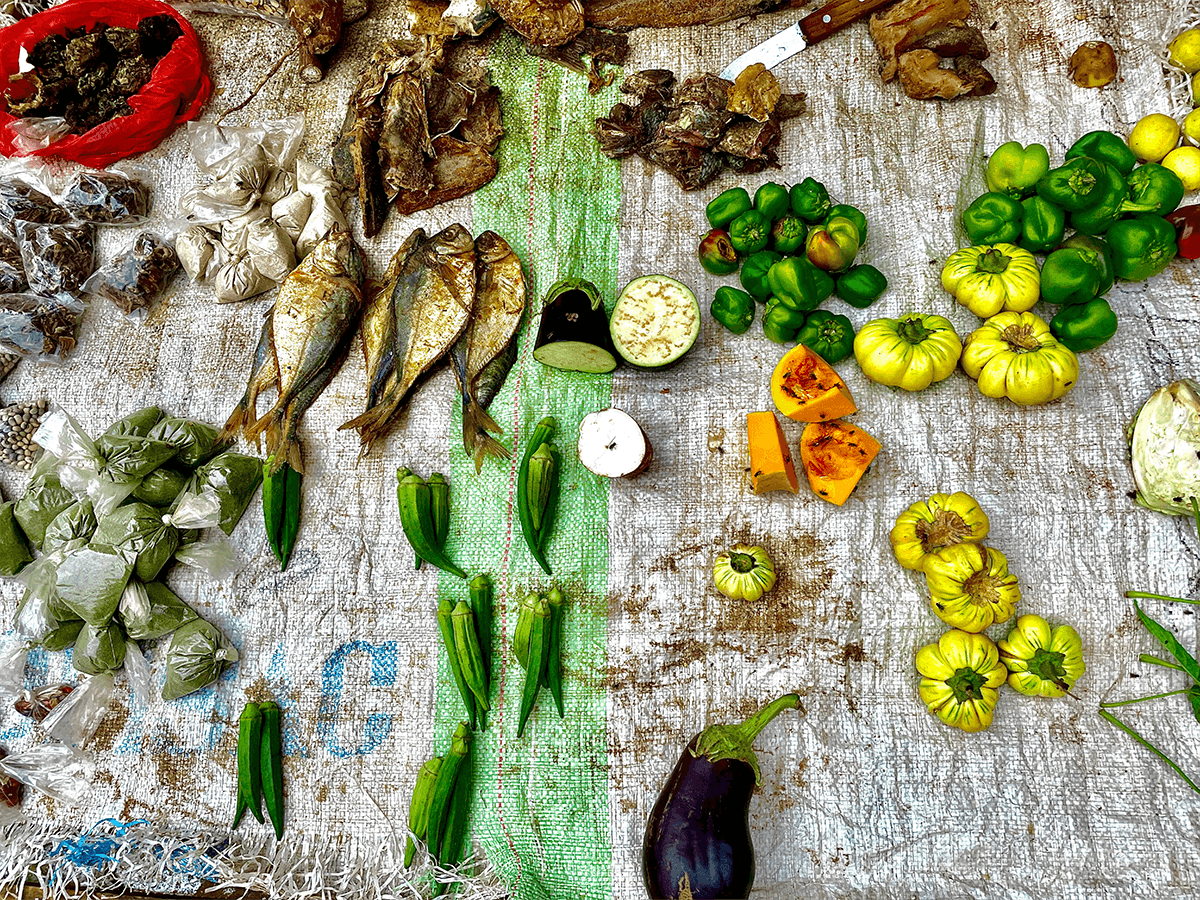

Extension agent Kim Hoffman selects food from a local farmers market to use in a cooking demonstration.

In 2012, Abaye shook a small orb from a seed packet into a Senegalese farmer’s hand.

Had he ever seen this before? she asked.

The farmer shook his head. He had never seen a mung bean in his life.

In reality, Abaye — or “Dr. Ozzie” as her legions of adoring students call her — knew the answer before she asked the question on that hot African day.

The professor and Extension specialist in the School of Plant and Environmental Sciences had spent several years assessing what would be the best crop to diversify the Senegalese diet.

And so, a project that married all the things she cared most about in life — agronomy and food security, children and empowering women — was born.

Abaye and others embarked on a USAID-ERA project to link research, education, and outreach that was designed to investigate the potential use of mung beans as a new crop to address malnutrition and food insecurity in Senegal. She looked into other warm-season legumes but none were climatically a right fit for Senegal. Abaye started thinking about mung beans.

She asked her counterparts at the Senegalese equivalent of Agricultural Research and Extension Centers if they ever grew mung beans. One of them brought her back to the room where thousands of small brown envelopes filled with seeds were stored. He dug out a packet of mung beans and told her a private company thought about growing mung beans but abandoned the project. Later that day, she took the brown packet and showed it to the farmer that had never seen such a thing.

“That was it. We didn’t need to do any more research,” said Abaye, whose voice carries the lilting Ethiopian accent of her childhood. “We found our bean.”

Video by Zeke Barlow

Professor Ozzie Abaye (center) conducts many of her meetings with local villages under the shade of a neem tree.

From 2013 to 2016, Andre Diatta (’16, ’20) was one of 14 Senegalese graduate students who made Blacksburg their home, which was made possible by the USAID-ERA project.

In between his beloved walks around the Duck Pond and soccer games on the Drillfield, Diatta was in the lab and at Kentland Farm, testing more than 550 lines of mung beans to see which ones would grow best in Senegal.

Though Diatta didn’t grow up in an agricultural family, when he looked around his country where food security was a major threat, he knew what he wanted to do.

“Getting into agriculture was trying to be part of the solution,” he said recently as he walked around the campus of Gaston Berger University in Senegal, where he’s now an assistant professor of agronomy.

Virginia Tech’s Ut Prosim (That I May Serve) ethos combined with the mung bean project was a perfect match, he thought. "This felt like an opportunity to give back and serve," he said.

Other students got involved in the project, too.

Mary Michael Lipford (’21) was one of three students engaged in mung bean research and outreach in Senegal. The students were funded by Counterpart International, the college’s Graduate Teaching Scholars Program, and Pratt Undergraduate Research Program.

Mary Michael Lipford, pictured with Abaye, trekked across the world to fight food insecurity in Africa, help farmers, and empower youth. Read Mary Michael's full story

Mary Michael Lipford, pictured with Abaye, trekked across the world to fight food insecurity in Africa, help farmers, and empower youth. Read Mary Michael's full story

Their work opened doors they never thought possible.

When Lipford came to Virginia Tech, she wanted to change the world – which seemed like a daunting task until she took a course with Abaye.

“I heard her talk about her mung bean research and how she helps empower women,” said Lipford, who traveled to a village in Senegal and helped hold a mung bean cooking competition. “I immediately knew that’s what I wanted to do.”

For a society to grow, Lipford said, it needs to have its basic needs met: food, water, health, and education. “If you can’t feed yourself, you can’t go anywhere or do anything,” she said.

To show what you can do with the mung bean, Lipford traveled to a village while in Senegal and helped hold a mung bean cooking competition.

The mung bean project involved other departments within the college and around the university. Kevin Kochersberger (’83, ’84, ’94) and Mary Kasarda from the Department of Mechanical Engineering designed a mung bean splitter for Senegal. Taylor Vashro (’16, ’17), a student researcher in the Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise, examined the effect of mung bean on women’s and children’s dietary diversity.

“When she eats mung beans, her breasts are full of milk and she’s saving money, because if you don’t have milk in your breasts, you have to buy formula for your infant,” Vashro reported one woman telling her.

After eight years, the project was a success – but it was also wrapping up. Abaye felt unsettled, like there was more work to be done.

The day that she heard that Counterpart International was seeking a partnership with a land-grant institution to pilot a nutritionally rich crop for their school feeding programs in Senegal, Abaye dashed home to work on her proposal.

Counterpart International — a non-profit that partners with other organizations to build inclusive, sustainable communities in which people thrive — was looking for someone to complement school meals with newly released mung bean seed varieties. The project was funded through McGovern-Dole-USDA Food for Education Program.

“Virginia Tech’s experience with developing mung beans made for a great partnership to help us further our mission of providing communities the tools they need to thrive and be sustainable,” said Kathryn Lane, chief of party for Counterpart in Senegal.

Over the next three years, teams from Virginia Tech, Virginia Cooperative Extension, and Virginia 4-H visited the West African nation more than a dozen times and collaborated with Counterpart International to pilot the mung bean project at 10 different villages.

From 2019-2021, more than 1000 kilos of mung beans were produced on two hectares of land, which provided school meals to 2,761 school girls and 2,006 boys.

But Mamadoe Thioye doesn’t need those hard facts to know that the mung bean project was a success in his village.

Ibrahim Thioye, 12, walked through the fields where the rainy season dumped a coat of verdant green over the normally dun-colored land. He passed the okra and casava growing in the sandy soil and golden birds flitted about the sky as he came to a plot where black pods dangled from ankle-high plants.

Ibrahim Thioye, 12, walked through the fields where the rainy season dumped a coat of verdant green over the normally dun-colored land. He passed the okra and casava growing in the sandy soil and golden birds flitted about the sky as he came to a plot where black pods dangled from ankle-high plants.

Just a few years ago, Thoiye had never eaten these mung beans that are growing, but now he can’t get enough of them.

“I can see the difference with the mung bean already,” his mom, Asyaia Thioye, said. “The children are physically stronger and it helps with indigestion.”

Andre Diatta, who is now a university professor in Senegal, earned his Ph.D. studying mung beans at Virginia Tech.

Andre Diatta, who is now a university professor in Senegal, earned his Ph.D. studying mung beans at Virginia Tech.

His village was one of the 10 pilot projects and one of the more successful ones. They are hungry for more. Over the last three years, Ibrahim’s father, Mamadoe Thioye, donated a few acres for the mung beans to be grown for the local school canteen.

Mamadoe Thioye, who is president of the local school board, said the mung beans can be harvested many times during the growing season and you can plant many successive crops due to their short growing time. They are easier to grow and more productive than the cowpea they have worked with for so many years.

And Thioye is seeing even better results than those found in the field. He said absenteeism is down in school because kids aren’t as hungry. And their standardized test scores are higher than they’ve ever been – a testament, he said, to the nutrition they are now getting from the mung bean.

But the mung bean project isn’t just feeding children’s bellies – it’s also feeding their minds.

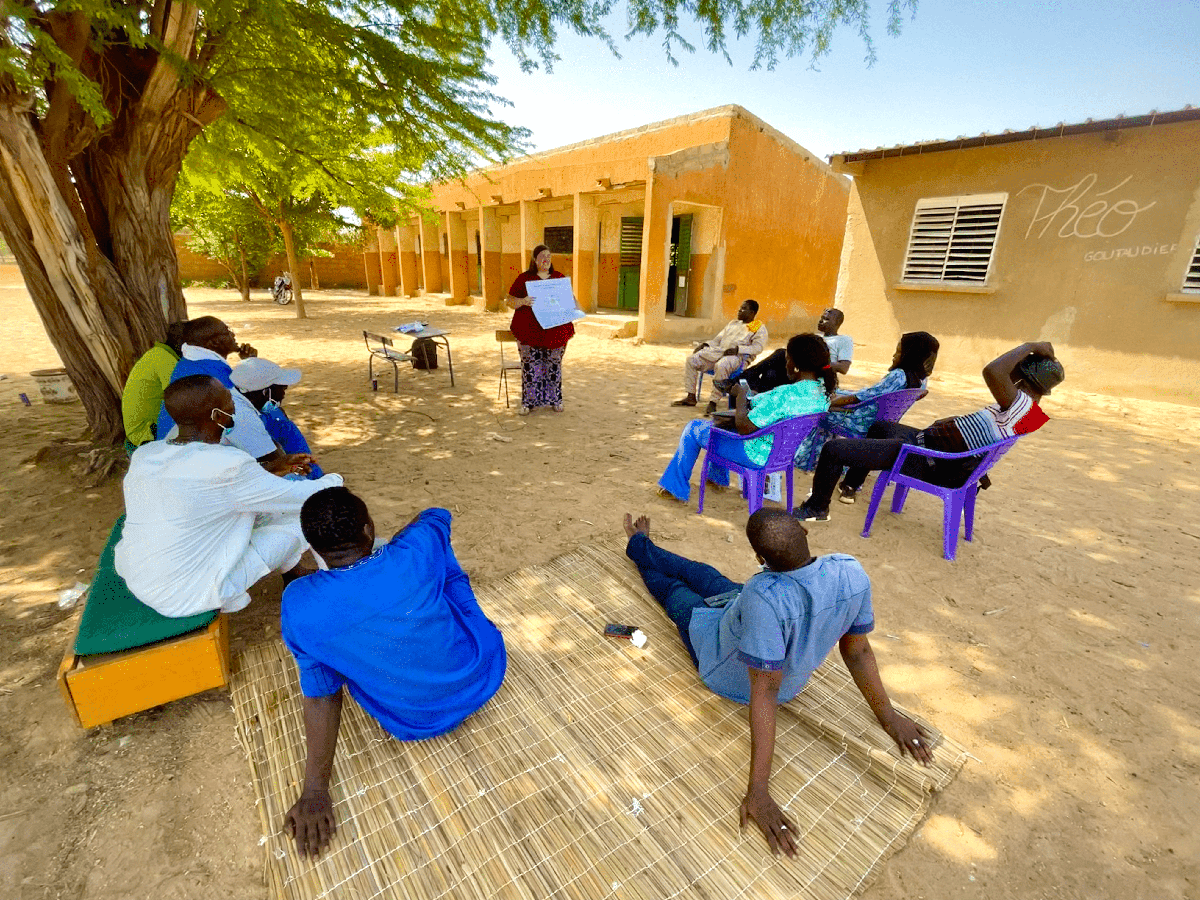

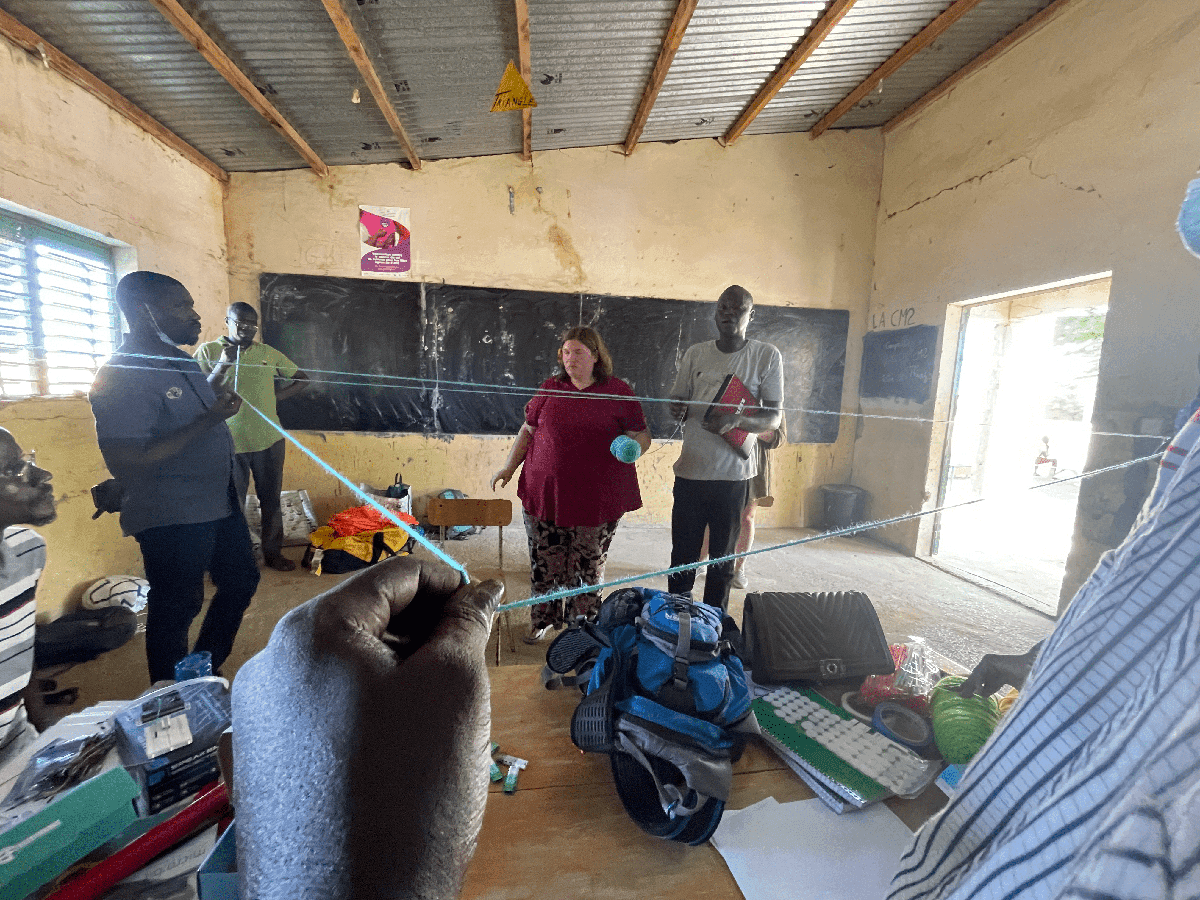

Erika Bonnett laid out an assortment of circuit boards, water pumps, and balls of yarn, and issued the teachers a challenge: take what you’ve got here and create a lesson for your students using only these materials.

The sound of afternoon prayers drifting in from the nearby mosque mixed with the chatter of excited teachers as they picked up the various electronics and started developing an impromptu lesson.

Over the last three years as Abaye and others were working in the fields to grow mung beans, Bonnett, a Virginia 4-H education specialist, has been in Senegalese classrooms collaborating with teachers on developing a STEM-based experiential learning curriculum around the mung bean. Before this, much of their learning modules had been theory or teaching from a book. But Bonnett knows first-hand the value of the 4-H model of learning by doing.

Bonnett grew up in a small, poor mining town in West Virginia where opportunities were limited. She became involved in 4-H through opportunities with her local club and grew her leadership ability at state and national 4-H events. She was hooked on 4-H so much so that the lessons stuck with her through her Ph.D. and now, as a leader of educational program development for the state’s more than 200,000 youth involved in Virginia 4-H.

During her time in Senegalese classrooms, Bonnett has worked with teachers to develop STEM education curriculum.

Swipe left for more

Mamoune Niang, the headmaster of the school at Thiago where Bonnett was conducting the program that day, said the lessons have been invaluable.

“In the past, our science was focused on theory,” Niang said. “But with this program they have the chance to practice what they are learning. They have an interest in science because they are having hands-on learning.”

Over the last year, three Extension agents visited Senegal to teach everything from food safety to good nutrition, including Kim Hoffman, an agent from Stafford County. She was there recently to share messages on healthy eating much like she does back home, where she works with schools to help children make healthy choices.

Hoffman translated a series of posters on safe food handling process into French and shared best practices with a group of cafeteria workers. She explained how colorful vegetables are the key to a healthy diet and spoke about how the mung bean was high in iron and helps blood to clot after a cut. The woman nodded in appreciation as a gas stove in the corner hissed, cooking up a fresh pot of mung beans.

As Bonnett and Hoffman’s time with the group was winding down, so was the project in Senegal, but Niang said the hands-on problem-solving lessons will continue long after the team returned to Virginia.

“Thank you for your friendship and all that you have done for Senegal,” Niang said as they hugged goodbye. “It is not a small thing that you have done.”

Bean by bean, Amadou Saydou Sow measured out his harvest. When one fell to the ground, he carefully picked it up and placed into back in the bag to be measured. He’d worked too hard to let one bean escape.

Of all the villages that Abaye has worked with over the last few years, Sow’s Thiewle has been the most successful. The 140 kilograms of mung beans from a quarter of a hectare that Sow was weighing out was all the proof that was needed.

These beans are the result of some of the new open pollinated lines being screened by Senegal’s Research Institute from 600 lines that are expected to be the best mung bean varieties for Senegal. Sow, who is the head of the local school board, has fed his new-found food to the children of the village and has produced so much he’s able to sell the seeds to other villages, where the work can begin anew.

“Long after Virginia Tech is gone, we will continue this project,” said Sow, whose undershirt had the spires of Burruss Hall peeking out of it.

Ever the agronomist, Abaye wanted to know everything about his harvest. How much did he water it? What inputs did he use? What other crops were grown nearby? How many times did he plant it? When Sow wasn’t able to breach the language barrier when talking about his favorite variety of mung beans, he used his fingers to draw a picture in the sand.

This village has been more to Abaye than just a test subject. She’s part of it now. The day she learned her sister died, the village wrapped its collective arms around her. Abaye built and named the school’s kitchen in her parents’ honor. Children chant her name when she arrives after being away for months.

For it is here, in this remote West African village, where all the things she has devoted her life to — children and education and agronomy — have come together in the form of one little bean. The fruits of this labor will be reaped for years.

“Feeding the children is feeding the community,” Sow says as the two say goodbye. “Only God knows how happy we are.”

Max Esterhiuzen contributed to this story. Youssoupha Gueye assisted with translations.